The ‘Golden Age’ of the Brao People in Northeast Cambodia

AKP Phnom Penh, January 05, 2021 --

The Brao people of northeastern Cambodia played a key role in fostering regional cooperation in the 1970s through their close ties with Vietnamese and Lao leaders. Dating back to the early 1950s, such collaboration had significant national consequence which, a new book agues, allowed the Brao to enjoy a golden age during the period of the People's Republic of Kampuchea between 1979-1989.

As a joint Vietnamese-Cambodian military offensive against Pol Pot was fully underway 42 years ago in early 1979, senior defectors who fled the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime met in Vietnam. It was Jan. 5 — two days before the Liberation of Phnom Penh. At the time, Samdech Akka Moha Ponhea Chakrei Heng Samrin was chairman of the United Front for the National Salvation of Kampuchea, which had just held its inaugural congress in Cambodia near the Vietnamese border the previous month. He remembers the Jan. 5 meeting well. Now Speaker of Cambodia's National Assembly, Samdech Heng Samrin had led a group of Cambodians in fleeing to Vietnam to escape Pol Pot’s killings in 1978. Among those who also defected were fellow military commanders Samdech Akka Moha Thamma Pothisa Chea Sim, the future Senate President, and Samdech Akka Moha Sena Padei Techo Hun Sen, the current Prime Minister who succeeded Samdech Chea Sim as head of the Cambodian People’s Party following his death in 2015.

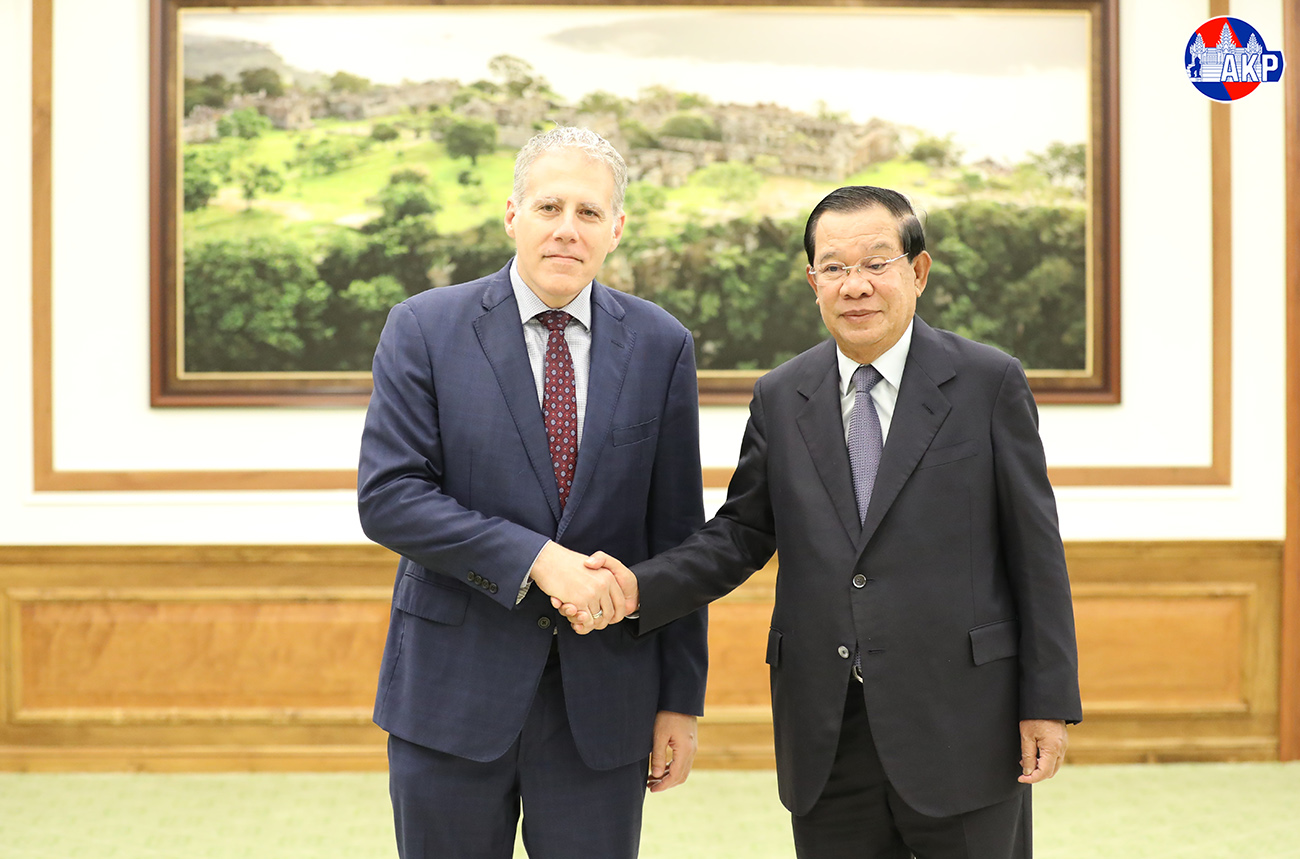

Leaders of the Khmer People's Revolutionary Party in 1981. Samdech Heng Samrin (center) served as the General Secretary of the Party and President of the State Council. Politburo member Bou Thang, seated on the left, was elected to the National Assembly representing Preah Vihear Province in 1981. He became defense minister the following year. (Photo: Bou Thang)

The meeting in Vietnam on Jan. 5, 1979 was a congress to re-establish the Khmer People’s Revolutionary Party, which had been hijacked by Pol Pot and renamed as the Communist Party of Kampuchea. “All generations were there, and so the entire country was represented,” Samdech Heng Samrin wrote in his memoirs published in 2013. “I still remember there were four groups — the first led by me with Chea Sim; the second led by Hun Sen; the third, led by Pen Sovann, who had been living in northern Vietnam; and the fourth led by Bou Th(a)ng, the ethnic minority leader.” The four military commanders were among eight Cambodians who drew up an 11-point plan for the United Front announced by Samdech Heng Samrin on Dec. 2, 1978. The three others were Ros Samay, the general secretary of the front, and another two ethnic minority leaders — Bun Mi and Soy Keo.

How three ethnic minority leaders come to play such a defining role in overthrowing Pol Pot and helping to rebuild Cambodia from scratch from 1979 to 1989 is the subject of a fascinating new book by Ian Baird, a professor of geography at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Baird, also director of the university’s Centre for Southeast Asian Studies, has conducted extensive research in northeast Cambodia, Laos and Thailand since 1990. Based in Champasak province in southern Laos for 15 years, he was the first scientist to carry out comprehensive monitoring of fish migrations across the Khone Falls near the Cambodia-Lao border. He has also conducted detailed research into ethnic minorities in the region.

Northeastern Cambodia in the 1990s

Map: Ellie Milligan and Meghan Kelly/Cart Lab/Department of Geography/University of Wisconsin-Madison

Baird's book focuses on the Brao people who mainly live in Rattanakiri and Stung Treng provinces in northeast Cambodia and neighbouring Lao provinces of Attapeu and Champasak. There is also a Brao village in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. Overall, more than half of the estimated total population of 65,000 resides in Cambodia, especially in upland areas along the Sesan River. This is a major tributary of the Mekong which — together with the Sekong River and Srepok River — forms the so-called 3S system, an important spawning area for many migratory fish species.

In Taveng and O Chum districts in Rattanakiri, the northeastern province which borders both Laos and Vietnam, Brao people are the main ethnic group. Baird, who speaks both the Brao and Lao languages, has based his book on multiple interviews with Brao and other ethnic minority leaders in northeastern Cambodia over two decades.

The author recounts how Bun Mi — one of the 14 founding leaders of the United Front in 1978 — emerged as the Brao leader of the Khmer People’s Revolutionary Party in Rattanakiri in the early 1960s. The party was formed in 1951 after the Indochina Communist Party dissolved into separate Cambodian, Lao and Vietnamese parties to fight French colonial forces. According to Baird, “many Brao and other ethnic minorities in Rattanakiri province supported the Vietnamese in fighting against the French.” By the time of the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, “some Brao and members of other highland ethnic groups in the northeast had BECOME heavily involved in the communist struggle.” But they had no sanctuary in Cambodia — unlike revolutionaries in southern Laos who traveled to northern Lao provinces bordering North Vietnam to organise party activities.

Cambodian territory was adjacent only to South Vietnam, not North Vietnam. So thousands of Cambodian communists travelled by foot to Hanoi. Among them were Bou Thang and Soy Keo, childhood friends from Voeunsai, a district located on the Sesan River in Rattanakiri province. Bou Thang was half Lao and half Tampuon, another ethnic group in the northeast. Soy Keo was half Tampuon and half Kreung, a Brao sub-group. According to Baird, “there were apparently about one hundred Cambodian-born insurgents from Rattanakiri who made the trip to North Vietnam.” There were no Brao among the regroupees, “but there were thirty ethnic minorities in total, including some Kreung, Tampuon, and Jarai, and many ethnic Lao.” Both Bou Thang and Soy Keo received military training in the northern Vietnamese province of Bac Ninh near Hanoi in 1962.

Back in Rattanakiri, the Brao leader Bun Mi was undertaking a party-recruitment drive among revolutionary cells from the war against the French that were being revived in Voeunsai. In 1962, Bun Mi became one of the first Brao to flee to the forest with the revolutionary forces. He later became party secretary in the district where he was born — Taveng, located on the Sesan River upstream from Voeunsai — and a deputy military chief in charge of a sector.

With a large group of Cambodians who had been studying in North Vietnam since 1954, Bou Thang and Soy Keo returned by foot to Rattanakiri in 1970 — the same year that late king Samdech Preah Norodom Sihanouk was overthrown in a coup by Lon Nol, the Prime Minister. Pol Pot, who was by this time based in northeast Cambodia, “was immediately wary of these Cambodians because they had spent many years in Vietnam,” writes Baird, citing a senior Brao soldier who had studied politics under the Khmer Rouge leader. Despite such antipathy towards the returnees, Bou Thang became deputy leader of the military in what was now being referred to by the Khmer Rouge as the Northeastern Zone. His superior was Son Sen, who later served as defense minister in the Pol Pot regime between 1975 and 1979. As for Soy Keo, he was put in command of a company that later became a battalion.

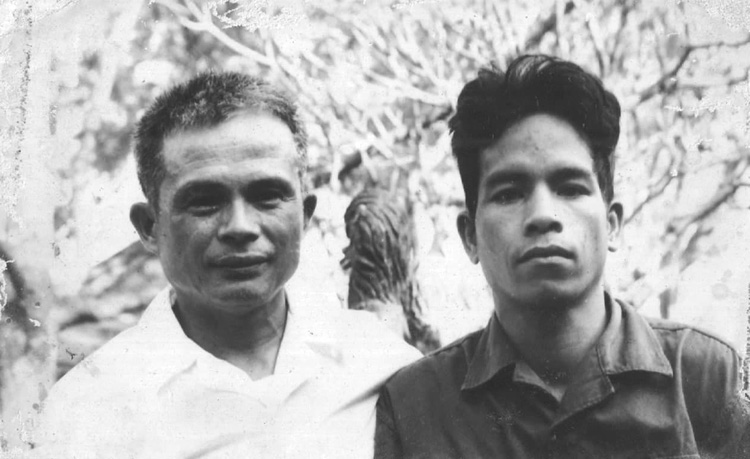

Brao revolutionary leader Bun Mi (left) with Vietnamese advisor Thanh Van in the central Vietnamese city of Danang in 1978. Bun Mi was one of the 14 leaders of the United Front for the National Salvation of Kampuchea founded in 1978 to overthrow Pol Pot's forces. (Photo: Bou Thang)

Amid growing discontent with Pol Pot’s forces, Bou Thang and Soy Keo considered defecting from the Khmer Rouge and fleeing back to Vietnam in 1974. A small group of Brao had already done so in 1973. “Although some Brao were among the earliest and strongest supporters of the Khmer Rouge, they gradually became disillusioned and disenchanted with the Khmer Rouge’s increasingly strict and draconian policies,” writes Baird.

A conflict between the Khmer Rouge and Bun Mi led to a mass exodus of Brao in 1975. “Most of the Brao living in the Sesan River basin, as well as some Tampuon, Kreung, Jarai and ethnic Lao people (fled) to Vietnam and Laos where they became political refugees.” According to Baird, they included “virtually all” of the Brao in Taveng district. In Vietnam, the refugees were allowed to establish a new commune at Gia Poc in the Central Highlands. It was located in Sa Thay, a district adjacent to Rattanakiri in what is now Kontum province. In Laos, they were settled in existing villages in Attapeu province, mostly in ethnic Brao communities. Back in Cambodia, Pol Pot’s forces took control of Phnom Penh on April 17, 1975.

Over the next two years, Vietnam’s relations with the Pol Pot regime deteriorated as Khmer Rouge forces launched attacks across the border. The Vietnamese decided to start organising the refugees at Gia Poc and a Northeastern Cambodia Insurrection Committee was set up.

Amid further worsening of relations, the Pol Pot regime severed diplomatic ties with Vietnam at the end of 1977. By March 1978, the Vietnamese military made it clear it would support Cambodians taking refuge in Vietnam. In Khmer-language broadcasts, Radio Hanoi soon started openly encouraging Cambodians to rise up against Pol Pot. According to Baird, the situation became “especially tense” after Pol Pot’s forces purged the Eastern Zone. Samdech Heng Samrin, who would soon be defecting to Vietnam himself, describes the fighting in detail in his memoirs including the killing of Eastern Zone Commander So Phim, who was accused of being a traitor. According to Samdech Heng Samrin, Pol Pot’s forces also killed So Phim’s wife, two of their children, a regional party secretary and the logistics chief for the Eastern Zone.

Bun Mi travelled to Vientiane to meet with senior Lao leaders and tried to get support from refugees in Attapeu province. Soy Keo made a similar trip to the Lao capital to meet General Osakanh Thammatheva, who was from Voeunsai and later became a Lao government minister and eventually a member of the Politburo of the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party. Soy Keo then went to Attapeu to see former colleagues. According to Baird, “no actual recruiting was done at this time, but preparations were well underway.” Soy Keo later led a third recruiting mission to the country, which by then was known as the Lao People's Democratic Republic. Although no Brao were ready to go to Vietnam, several ethnic Khmers accompanied him on his return to Vietnam. The fourth Lao mission was more successful, with about one hundred Brao living in Xaysettha district in Attapeu agreeing to join the Cambodian forces in Vietnam. They decided to take their wives and children with them. The group of 600-700 arrived in Gia Poc on Dec. 5 — three days after Samdech Heng Samrin announced the formation of the United Front and less than three weeks before the launch of the military offensive to topple Pol Pot’s forces.

The victorious liberation of Phnom Penh on Jan. 7, 1979 was accompanied by the establishment of the People's Republic of Kampuchea with an eight-member provisional revolutionary council chaired by Samdech Heng Samrin.

By May, 1981, elections were held for 117 seats in a new National Assembly. Ten of the elected members were from the four northeastern provinces. Nine were from ethnic minorities including three successful Brao or Brao sub-group candidates from Rattanakiri, Mondulkiri and Preah Vihear. Also elected from Preah Vihear was Bou Thang who had gradually succeeded Bun Mi as the most important revolutionary leader from the northeast as Bun Mi fell into ill health. Soy Keo was elected to represent the eastern province of Kratie. Baird notes that the Khmer People’s Revolutionary Party was “stronger than in other regions.

As for the northeast itself, ethnic Brao people were appointed as chairmen and vice chairmen of provincial people’s committees and secretaries of party committees in Rattanakiri, Stung Treng, Mondulkiri and Preah Vihear. They were also allocated most other senior military and civilian positions in the northeast. Considering that many had low levels of formal education, “it was necessary to immediately promote education so as to gradually build up human resources,” Baird writes. “There were no educational facilities in northeastern Cambodia at the time so many northeasterners were sent, at least for short periods, to study in Vietnam.” They were also sent to Laos, the Soviet Union and Eastern European countries.

By Sao Da